On the occasion of sixth Kashmir Expo that Kashmir Chamber of Commerce & Industry hosted for nearly 70 buyers from 21 countries, R S Gull offers a status report of Kashmir handicrafts that has not only dictated the global fashion trends but also helped the society survive the worst upheavals of history

“It is an effort towards creating a proper marketing platform with global linkages, developing design network required for change, offering buyer a direct access to artisan and managing a better pie in India’s overall handicraft export basket,” J&K’s finance minister Dr Haseeb Drabu said on October 22, 2007, the day Srinagar hosted the maiden handicraft buyer seller event. Then, he was state’s Economic Adviser. “This event is just a start to offer us a confidence that we are able to market ourselves.”

“It is an effort towards creating a proper marketing platform with global linkages, developing design network required for change, offering buyer a direct access to artisan and managing a better pie in India’s overall handicraft export basket,” J&K’s finance minister Dr Haseeb Drabu said on October 22, 2007, the day Srinagar hosted the maiden handicraft buyer seller event. Then, he was state’s Economic Adviser. “This event is just a start to offer us a confidence that we are able to market ourselves.”

But the news of that day was not dominated by Kashmir’s serious effort to reconnect with the larger world that has historically appreciated the exclusive artistry of people weaving dreams for centuries. The snippet that bigger newspapers front-paged was about 10 Americans buyers who dropped out at the last moment. They had acted upon the advisories that US mission in Delhi issued on the eve of the event. However, 52 other buyers including three agents for American retailers ensured their attendance.

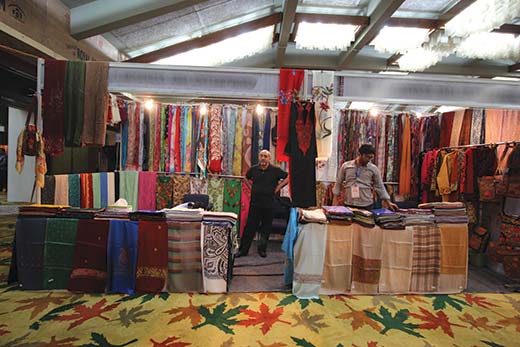

But change is immune to the utopian changelessness. On May 30, 2015 when the sixth meet was inaugurated by Chief Minister Mufti M Sayeed, buyers filled a portion of the SKICC’s main hall. As many as 67 buyers from 21 nationalities participated, including four from US. Kashmir Chamber of Commerce and Industries (KCC&I) that hosts the event in partnership with J&K Bank, state and the central governments, say the level of confidence of buyers has improved phenomenally over the year. A few of the buyers had come with their children as well.

The yearly event is gradually emerging into a handicraft festival. Stakeholders are envisaging this meeting to spread into a seasonal attraction, four times a year, to supplement tourism sector and becomes a larger event. After all, handicrafts are just not a mere trade for Kashmir; it is part of its heritage and, in a way, part of its faith.

But it is also a fact that the changes which started influencing Kashmir’s handicrafts from the day French straw-hat maker Joseph Marie Jacquard invented his famous Jacquard loom in 1810, are still in progress. He invented the loom to help Paris manage a local replica of the Kashmiri Shawl made famous by Joséphine de Beauharnais, the French Empress and one of history’s great style icons. Now, Kashmir is encouraging changes in its traditional system to stay relevant to the new market trends that is dominated by design, technology, authenticity, durability and, above all, the price.

Terming the event “a small step but a huge foray into future”, Mufti in his inaugural remarks sketched a literal SWOT analysis of the sector. During the “very difficult phase” (a reference to the turbulent 1990s) when nothing much was happening, Mufti said Kashmir survived on two things: horticulture and handicrafts. “I am proud of those golden hands who kept this exclusive art alive,” Mufti said.

Tracing roots of handicrafts to the Amir Kabeer Mir Syed Ali Hamdani days when Kashmir’s transition to Islam took place, and referring to the geo-strategic situation that ceased Kashmir’s status to be the gateway to Central Asia, Mufti talked about reviving silk route and using the crafts for reconnected with the overseas. For that he suggested improvement in the socio-economic status of the craftsman, halting the invasion of machine, separating real from fake while improving the production. For better competition and attracting the high-end customer, Mufti even wanted price tagging too.

Tracing roots of handicrafts to the Amir Kabeer Mir Syed Ali Hamdani days when Kashmir’s transition to Islam took place, and referring to the geo-strategic situation that ceased Kashmir’s status to be the gateway to Central Asia, Mufti talked about reviving silk route and using the crafts for reconnected with the overseas. For that he suggested improvement in the socio-economic status of the craftsman, halting the invasion of machine, separating real from fake while improving the production. For better competition and attracting the high-end customer, Mufti even wanted price tagging too.

“It is our joint responsibility to see that Brand Kashmir is safeguarded and fake products in the name of Kashmir Art are not only discouraged but totally wiped out,” Mufti said. “This can only be done with active participation of all stakeholders.” He reassured his government will promote the sector by introducing cluster approach, establishing common facility centres and design development, dove-tailing handicrafts with tourism, besides, facilitating access to credit and markets.

But part of the burden that states chief executive unveiled, may require a pro-active policy implementation from his government. Kashmir’s hospitality, handicrafts and the horticulture sectors (3Hs of Kashmir economy) have generally been driven more by the society itself than by the government. There have been series of initiatives in the handicrafts but generally they were stuck at the level of facilitation or implementation.

Khursheed A Ganai, the top officer looking after the industrial sector, voluntarily identified certain grey areas that require attention. While he identified the absence of dry port facility in the state as a key factor discouraging exports, he skipped mentioning the absence of institutional infrastructure – mostly run by the central government, in the state. Though Jairam Ramesh, the Congressman who headed the Commerce Ministry, had pushed a few developmental and export related institutions to restore its operations from Srinagar, quite a few have taken it seriously. “If we have to increase our share in the country’s overall export basket, we will have to do more,” Ganai said.

Authenticity is a key factor in handicrafts and the Geographical Indication (GI) is now the main barometer for this. It is a patent sort of sign or a name which listed products use to identify its place of origin and the use of particular raw material, processes, systems in its patterns or the history and traditions of the place linking directly to the product. J&K has fought a protracted battle in the GI registry to get what it possesses. Given the two halves of the state being in possession of two sovereign states, the contest on GI issues was stiff. Barring Kani Shawl, a peculiar expensive product endemic to the artistry of Kashmir, almost every request for GI to every other product was contested.

Thanks to Mohammad Sharique Farooqi, the erstwhile Director of the Craft Development Institute (CDI) who spent an enormous time and energy in managing six GIs for the state. By now, Kani Shawl, Kashmir Pashmina and Kashmir Sozni Craft (all in 2008-09) have GIs and in 2011-12, Kashmir got three more GIs for Papier Mache, Wood carving and Khatamband. Right now the only application from J&K that is pending disposal before the Registry in Chennai is Basmati in which many other states have also applied. What about other crafts? Kashmir carpet that holds the lion’s share in the overall handicraft exports is still not a GI product! The problem is that after Farooqui was unceremoniously ‘banished’ from J&K, there was no follow up to the processes he had initiated.

But that is not even part of the story. Getting a GI in Bangalore for our products continues to be a useless exercise as long as a similar process is not initiated in the particular products off-shore markets. A process for registrations of GIs in 26 European, 20 Asian, 15 Russian, 11 Middle Eastern, six other countries in South Africa, besides USA, Mexico and Canada had started. Can anybody hazard a guess about its current status?

GI to Kashmir Pashmina had become a handy tool for the policymakers to ensure the quality issue. CDI evolved a system as early as August 2013 and the then Chief Minister Omar Abdullah drove to Bagh-e-Ali Mardan to throw the Rs 4.40 crore Pashmina Testing and Quality Certification Center (PTQCC) open.

The process involved implanting a square-inch long Secure Fusion Authentic Label (SFAL) having a covert (read it under UV light) and overt (visible) information, besides, a unique number for tracking and records. The label costing Rs 150, a piece, gives the Shawl a global authenticity. It carries invisible nano particles, the micro-taggant and a unique code that can be read under infra-red light. This sub-microscopic chip, a forensic technology, can neither be copied nor destroyed by dry clean, washing or ironing. Kashmir is barely a quarter away from the second anniversary of the chip launch. How many shawls were tagged in this facility having the capacity to manage 250 thousands pieces a year? 15 shawls, so far! Officials said people are more interested in testing the raw material quality rather than tagging despite the fact that it is expensive, Rs 700 a test. They say after Farooqi’s ouster, CDI is literally crippled. It even lacked funds to participate in the Expo!!

Had officials permitted CDI to continue with efforts it was entrusted, by now, this facility might have come closer in standards to the nearest other facility that is in Hong Kong.

J&K, according to Chief Minister, sold handicrafts worth Rs 1700 crore last fiscal of which Rs 1200 crore is the direct overseas export. Had quality issues in Shawls been addressed, the basket might have grown bigger by now.

Poshish, the Kashmir tweed has been a vital local handicraft for centuries that has local raw material and market. A bit of improvement in the processes would help it compete with the Scottish tweed. A process was initiated in fact. It should have ideally led to the GI but things have actually reversed in last few years. Now, the J&K Handloom Development Corporation is using imported yarn (at least last year), and not local wool, in the making of Poshish.

J&K produces nearly seven million kgs of wool a year but lacks capacity to process even ten percent of it! A project aimed at wool processing including spinning and creating blends sanctioned by the development commissioner of Handlooms, Ministry of Textiles GoI, for implementation by Handloom Development Corporation (Poshish) could not happen fully from last six years because of bureaucratic hurdles.

J&K produces nearly seven million kgs of wool a year but lacks capacity to process even ten percent of it! A project aimed at wool processing including spinning and creating blends sanctioned by the development commissioner of Handlooms, Ministry of Textiles GoI, for implementation by Handloom Development Corporation (Poshish) could not happen fully from last six years because of bureaucratic hurdles.

Interesting part of the story is that Bemina Woollen Mills, a JK Industries owned facility, is marketing better coats than Poshish because it weaves on power looms and has slightly aggressive leadership, at least for a few years now.

Handloom Development Corporation had initiated an ambitious plan of identifying, copying and reviving the royal designs from Mughal and Afghan era. In 1999, its experts visited some of the global museums and art galleries to trace the designs and succeeded getting information about nearly 600 rare designs on basis of which it employed more than 120 artisans (90 of them ace craftsmen) and recreated 2300 masterpieces on 320 designs. They sold like hot cakes at fancy prices. So far 2193 pieces were sold for seven crore rupees of which Rs 3.45 crore was the wage component. Remaining 107 were devoured by floods. Demand is still there but supply stopped! Ideally this should have been done in association with the School of Design that once was handicrafts department’s prized possession. Remains exist but its essence is gone.

Carpets continue to hold the top berth in the handicraft basket but it is facing its own challenges. There have been two major interventions in carpet sector – the digitization of Taleem and improvement in the traditional loom. But that does not end the problems. Slump in international markets and cut-throat competition has blocked lot of capital in the exporter’s inventory thus impacting artisans.

Indian Institute of Carpet Technology (IICT) has initiated certain measures. It designed a new loom that is user friendly and the central government initiated the process of replacing nearly 40,000 traditional looms. In the initial phase 8000 looms were to be replaced but the progress in last three years is slightly around 3000! The IICT designed loom is manufactured by SICOP and distributed by Department of Handicrafts. IICTs design creation and their sale is picking up and its colour matching spectro-photometer is always working. Now, the IICT is planning a new semi-mechanized loom that can help weavers to weave woollen carpets faster and at low cost so that Kashmir can consider using its own manufacture. While it is a fact that Kashmir generally ill-affords the carpet it produces and prefers cheap Chinese and Iranian machine made, it has not given up weaving the dream. Another target IICT has is to create software that will help people calculate the costs of carpets. This will address a major concern of the buyers and consumers worldwide.

Trade is also quite restive over the allegations of being exploitative and is keen the government makes clear guidelines about the wages that artisans must get on sq ft basis. Besides, there are feeble voices within the trade suggesting since Kashmir lacks mass production base to sustain increasing off shore appetite, Kashmir carpet must follow Jamawars and Kani Shawls and emerge as an exclusive item fetching high yield at low supply. This, they say, is better than packaging Iranian carpets as Kashmiris. But to ensure it happens, lot of resources and consistent effort is required to re-brand the carpet and make it that exclusive. Every single carpet must have an elaborate certification system listing everything from raw material to the artisans.

Handicrafts must be encouraged to come out of the dingy rooms of artisans and the inventory of exporters to create its own narrative. It must be hand-held to get into a dialogue, to share its pains, list its priorities, seek its rights in socio-economic stratification, seek a formal market dedicated to the arts and eventually come out of the historic morbidity that Sikhs, Pathans and Dogras enforced upon it. Its stakeholders must be encouraged to create a level playing field within the trade and government must play the role of a facilitator in adopting the best practices and regulator in managing an even symbiosis. Perhaps this is history’s most crucial time when Brand Kashmir must get a push especially because China is keen to takeover part of the niche market. People may not know that some of the buyers who attended the Expo are Beijing bound, directly.

Despite these entire problems that history has consistently flagged throughout, handicrafts have survived, improved and remained competitive. Perhaps for the first time in history, it is more open to design-innovation, technology-intervention and keen to enter new markets on its own terms. In the just concluded meeting, buyers have recorded overall sale orders of more than one million US dollars. Mere presence of such a good number of buyers essentially indicates that everything was not washed away by September 2014 floods. But stakeholders must ponder over the fact that so many centuries after Kashmir embraced this Central Asian art, why handicrafts have not emerged as a full time profession.